Decades of archives, burnout, and ditching online noise to pursue offline creativity, travel, and a slower, intentional life abroad.

While packing for our move, I dug through boxes that span back to high school—friend‑written stories, doodles, poetry, slang lists, and word‑play games. I also uncovered every college paper, notebook, and printed email chain from the late‑‘90s through the birth of my son and the completion of my first master’s degree, along with articles, notes, old résumés, and CVs. After the mid‑2000s, everything shifted to digital storage.

Looking at those old emails, sketches, and lists, I’m struck by two things: the passion and ambition that drove me, and the scatter‑shot nature of my attention. Many projects were left unfinished, books unread, ideas half‑formed.

In my thirties, when parenthood, a full‑time career, and a second graduate degree converged, burnout set in. Digital copies multiplied, but they came with no guarantees: hard drives failed, email providers changed with each job, platforms vanished, and search tools proved unreliable. Economic shifts forced priorities, and a lot of content slipped away, leaving some dreams deferred.

My forties were spent in tech, raising my son, paying off debt, and moving out of state. Burnout lingered, yet surrounded now by my late father’s notebooks, my own archives, and our library, I was reminded that there is more than enough to explore and immerse myself in—whether or not I pursued professional work for others. The abundance of material, both personal and inherited, offers endless possibilities, giving me a sense of purpose beyond employment.

That realization has also changed how I approach time. I’ve begun curbing the habit of “frittering” my hours online, endlessly consuming other people’s content. There’s a lingering belief that deep focus on reading, drawing, or studying makes me “unavailable” to my family—or that I’m merely “escaping” rather than being productive. That judgment feels almost Protestant‑era, reminiscent of the way Jane Austen’s characters are scrutinized for their choices.

For years, I equated online activity—social media posts, chats, data exchanges—with being “social” and “real.” I treated the digital realm as if it were as tangible as a café table or a sketchbook—its fleeting likes and comments offering instant, almost physical feedback, feeding my craving for connection and validation, even though all I was really producing was a paycheck for the platforms.

But it wasn’t just the lure of the screen; it was also the loss of a social ritual that had shaped my youth. After the turn of the millennium, cafés stopped feeling like true gathering places. Today, when I step into one, most people are glued to laptops or phones, each lost in their own online world.

I miss the 1990s, when a trip to a café meant meeting friends, lingering over espresso, and talking for hours while the hum of the grinder provided a soundtrack. That café culture—the spontaneous conversation, the clink of cups, the shared silences—was a touchstone of my upbringing.

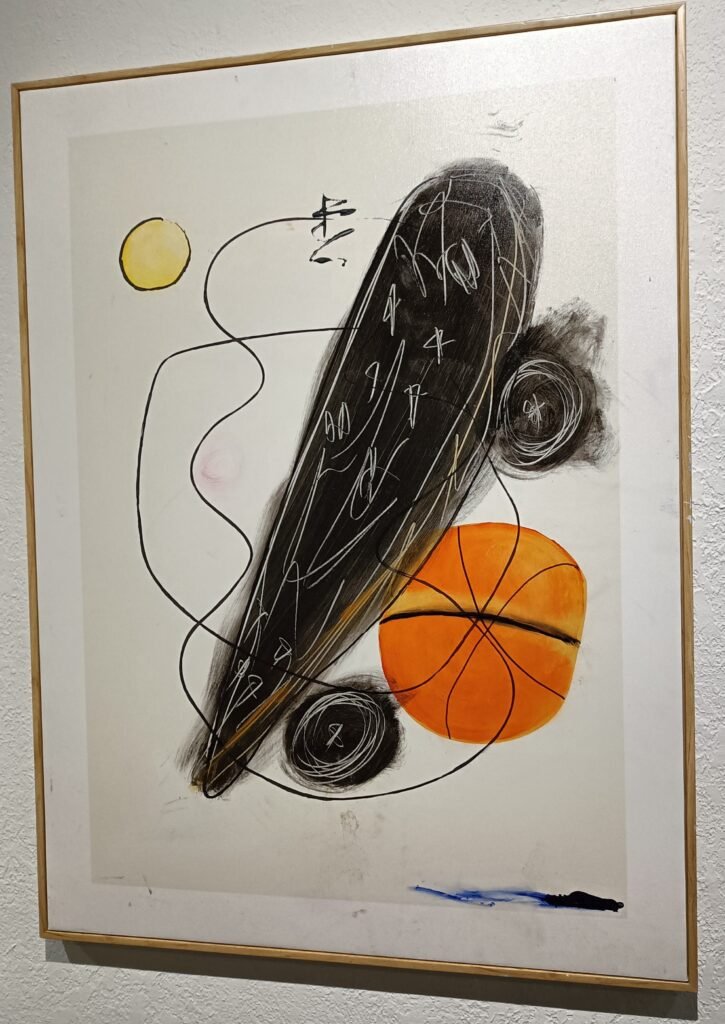

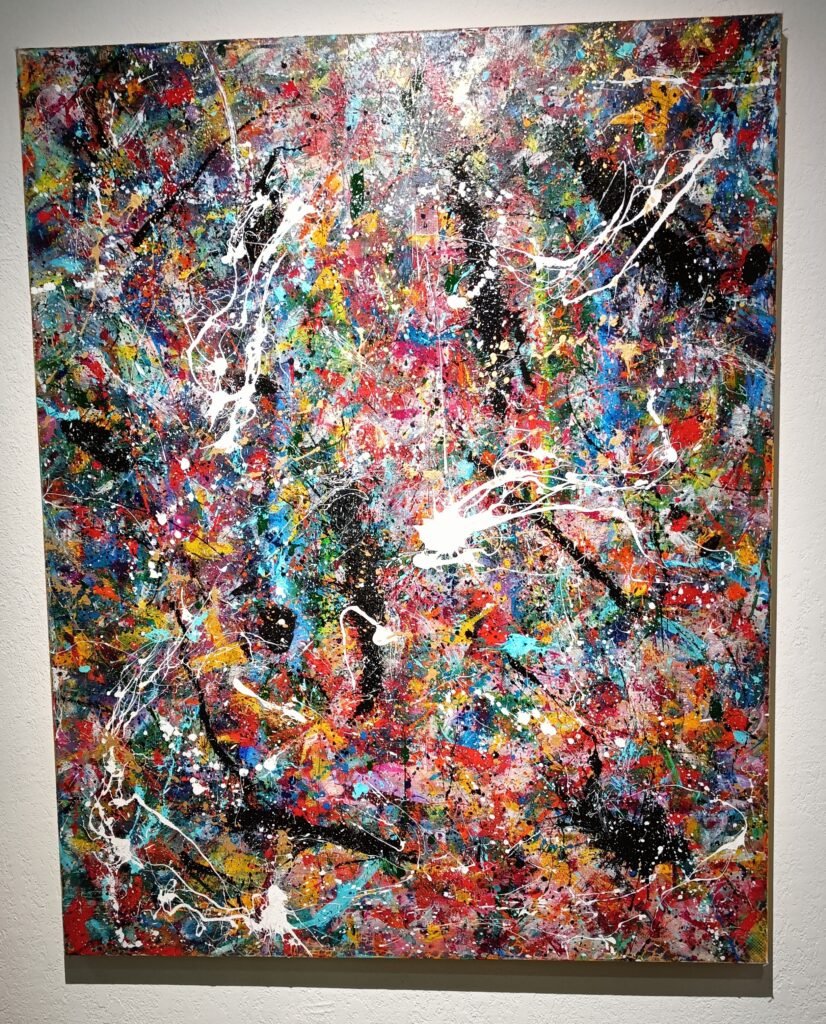

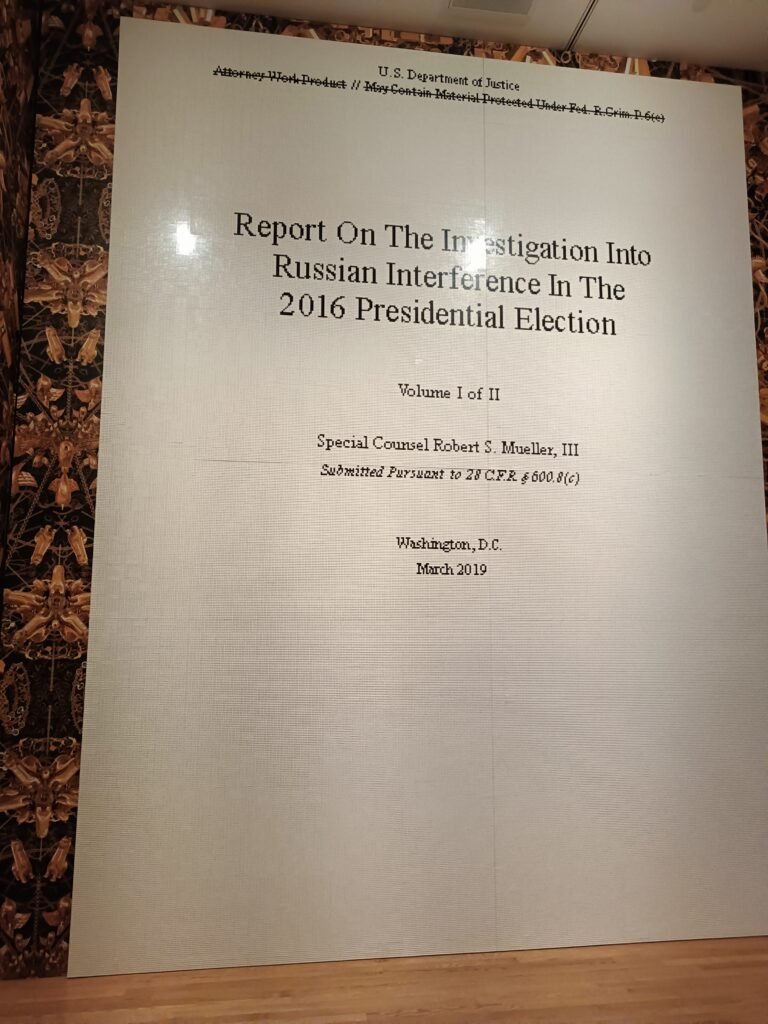

It’s exactly that experience I’m eager to rediscover when I move to Europe. My plan is simple: I’ll spend my days reading, writing, and making art in cafés. I’ll revisit my archives, travel, write about exhibitions and performances, and finally give those unfinished projects a chance to breathe. Surrounded by both my own work and the material I inherited, I know there will always be enough to keep me absorbed, on my own terms.

NOTES:

If you enjoy my writing here, you might also like some of my other projects:

- 💡 I have a Patreon where I share extra writing, behind-the-scenes notes, and updates on creative projects. You can check it out here.

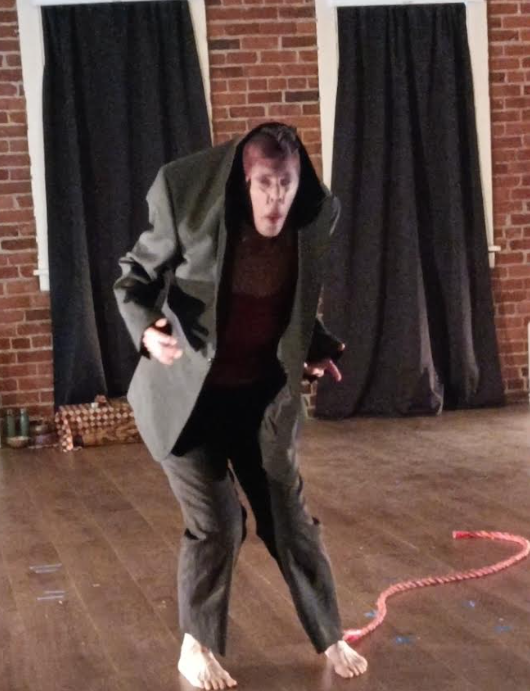

- 📖 I recently self-published my MA thesis on Butoh, which is available here. If you’re curious about performance, embodiment, and cultural history, I’d love for you to read it.

- 💸 Or, if you’d like to give a smaller one-time tip ($3), you can do so via Ko-fi [here]. Every bit of support helps and is greatly appreciated!